04-07-2025

The Geometry of God: How the Pantheon Turns Math into Magic

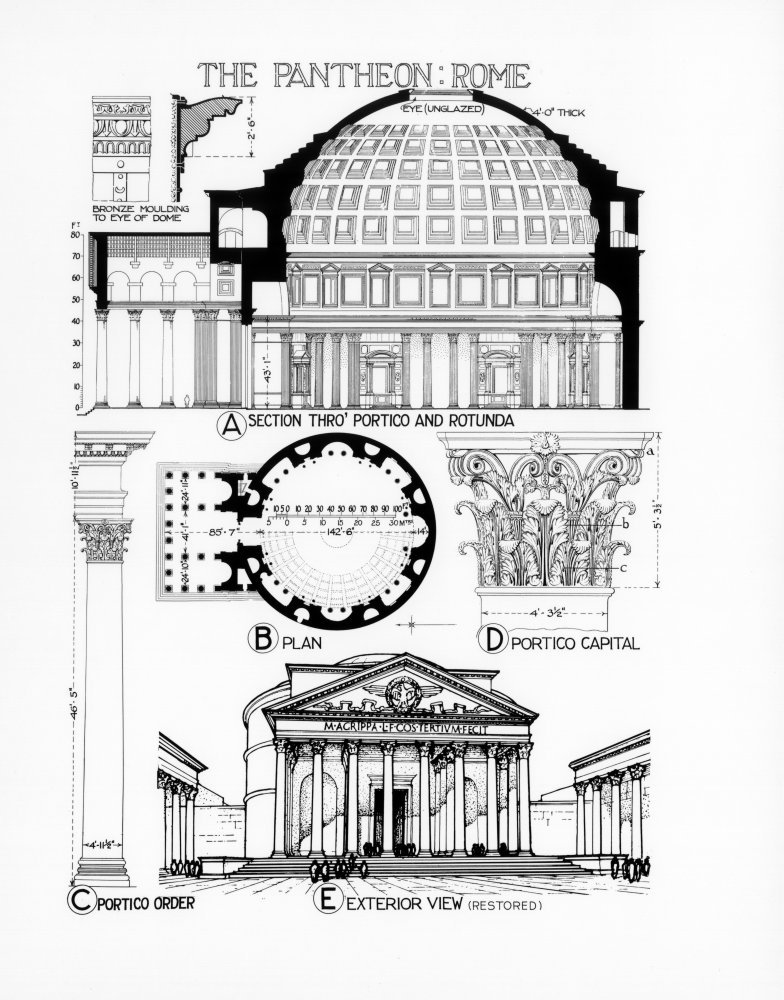

Detail of Relieving Arches: An illustration focusing on the brick relieving arches within the rotunda walls. These arches redirect the weight from the openings to the sturdy piers, showcasing the Romans' understanding of load distribution.Isometric View of the Dome's Coffering: This perspective illustrates the diminishing size of the coffers as they ascend towards the oculus, emphasizing the techniques used to reduce weight and enhance the dome's structural integrity.Cross-Section of the Pantheon: This drawing reveals the internal structure, highlighting the rotunda walls, niches, and the dome's coffering. It illustrates the relationship between the solid piers and the open spaces, demonstrating how the weight is distributed.Giovanni Battista Piranesi's etching titled Interior View of the Pantheon, part of his Vedute di Roma series. Created around 1768, this work offers a detailed depiction of the Pantheon's interior, framed by the portico's Corinthian columns.Photo: Marco Guinter AlbertonThe Reichstag Dome at Night – Transparency and Democracy in ArchitectureThis striking nighttime photograph captures the iconic glass dome of the Reichstag building in Berlin, Germany, designed by Sir Norman FosterThe Pantheon in Rome is not just a building. It’s a riddle wrapped in a sphere, encased in a cylinder, and solved through sheer geometric elegance. For all the talk of Roman engineering, imperial politics, and religious symbolism, the true genius of the Pantheon lies in its mathematical choreography—a composition of shapes and proportions so precise, so sublime, it’s as if the gods themselves sat down with compasses and calipers and whispered, “Let there be form.”

Start with the big one: the dome. It's not just big—it's perfectly big. The height from the marble floor to the oculus at the crown of the dome is 43.3 meters. The diameter of the dome itself? Also 43.3 meters. Coincidence? Not a chance. The Pantheon’s interior space forms a perfect sphere that could nestle inside the rotunda like a divine Russian doll.¹ It’s as if the architect—likely under Hadrian’s supervision, and possibly influenced by the likes of Apollodorus of Damascus—set out to bottle the cosmos. And succeeded.

The Romans, famously pragmatic, didn’t play with shapes for fun. Geometry was power, and the sphere was the ultimate symbol of divine perfection—no beginning, no end, just pure, celestial symmetry. Enclosing a sphere within a cylinder wasn’t just clever—it was cosmological theater. The dome becomes the vault of heaven; the floor, the realm of mortals. And connecting them both is the oculus: a nine-meter-wide open eye in the center of the dome that doesn’t just let in light—it summons it.

As the sun arcs across the Roman sky, the oculus becomes a moving spotlight, sweeping across the interior like a celestial metronome. In the morning, the light cuts across the entrance. At noon, it floats high above in the upper coffers. By evening, it sinks toward the apse. The building is, quite literally, a solar calendar rendered in stone. And it’s not just pretty—it’s precise. On April 21, the legendary founding day of Rome, the midday sun shines directly on the entrance, illuminating the threshold like a cosmic birthday candle.² You don’t need an inscription to know Rome ruled the world—the light tells you.

But there’s more. The Pantheon’s geometry isn’t limited to spheres and circles. The floor plan itself is a circle inscribed within a square—a classical proportion system known as ad quadratum.³ This motif—circle within square—has long been a symbol of the relationship between heaven (the circle) and earth (the square), echoed centuries later by Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. The entire spatial composition, from the portico to the apse, hums with modular harmony. Every niche, every column, every void lines up like a note in a divine chord.

And then there are the coffers—the sunken square panels in the dome. Beyond their decorative rhythm, they serve an important structural function: reducing the weight of the concrete dome. But their placement isn’t arbitrary. Some scholars suggest they follow a kind of logarithmic spacing, thinning toward the oculus and creating the illusion of height and lightness.⁴ It’s architectural sleight of hand—ancient, analog, and astonishingly effective.

Of course, no conversation about classical design is complete without someone whispering: “Golden ratio?” And in the case of the Pantheon, that whisper isn’t totally unfounded. While there’s no definitive proof that the building strictly follows the Golden Ratio (1:1.618), many of its proportions closely align with it.⁵ The width of the portico to the height of the dome, the relationship of the drum to the rotunda, even the spacing of elements in elevation—all seem to flirt with this most mythical of ratios. Whether intentional or intuitive, the effect is unmistakable: the building feels right. Balanced. Harmonious. Like nature itself designed it.

The building’s modular logic extends beyond aesthetics—it’s deeply structural. The weight of the dome is carried not by the drum alone, but by a hidden system of relieving arches, hollow chambers, and layered materials.⁶ Heavier concrete (with basalt aggregate) sits at the base of the dome, while lighter materials (like pumice) form the uppermost layers. Geometry guides not just the form but the performance of the structure. It’s as if the Romans reverse-engineered gravity.

And therein lies the magic: the Pantheon uses pure geometry not just to stand up, but to stand apart. It doesn’t rely on flamboyant ornament or ostentatious sculpture. Instead, it dazzles with form. It’s the same kind of thinking that would later inspire Renaissance architects like Brunelleschi, who all but lived inside the Pantheon before designing his dome for Florence Cathedral.⁷ It influenced Michelangelo, who borrowed its scale for St. Peter’s and called it “angelic, not human.”⁸ Even Le Corbusier, modernism’s cantankerous prophet, held it in reverence. In Toward a New Architecture, he praised the Pantheon’s "inspired geometry" and placed its image beside a modern car engine—declaring both as triumphs of form driven by pure logic.⁹ Norman Foster, too, once said that stepping into the Pantheon was “like entering the engine room of Western architecture”—a place where pure form generates emotional power.¹⁰

Walk into the rotunda, and the space doesn’t just open up—it unfolds. You are no longer in the hustle of Rome, dodging scooters and selfie sticks; you are in a stillness that feels suspended between time and gravity. The air changes. Your footsteps slow. The dome above, so enormous it defies logic, is somehow silent, poised. And then you look up—inevitably—to the oculus, the round aperture at the crown of the dome, and something shifts inside you.

The oculus is a pure architectural device, but it behaves like a celestial one. As the sun travels across the Roman sky, it casts a beam of light that sweeps across the interior like a sundial’s hand. In the morning, the light slices diagonally across the floor, hitting the lower walls and niches. By noon, it glows high on the upper dome coffers, diffusing the space with an ethereal silver. In the late afternoon, the beam lowers again, illuminating statues, columns, or maybe—if you’re lucky—a dust particle hanging in its orbit like a tiny satellite.¹¹

This moving spotlight transforms the building into a theater of time. It doesn’t just illuminate—it animates. The Pantheon becomes a kinetic object, not through technology, but through the deliberate choreography of sun and stone. And because the oculus is open to the sky, rain falls through it, too. On wet days, droplets fall like divine punctuation, landing on the ancient marble floor, where hidden drains in the center quietly whisk them away. There’s something strangely calming in knowing the building is open to weather, that it breathes with the seasons.

And then there's the sound. Unlike the reverberant echoes of Gothic cathedrals, the Pantheon’s acoustic is surprisingly gentle. Conversations are hushed by the dome’s geometry, and there’s a soft, warm tone to every step and whisper. It's not silent—but it feels serene, like a great, echoing thought just on the edge of being spoken.

At different times of day, the atmosphere shifts dramatically. A midday visit offers clarity: strong light, sharp shadows, geometry in full command. But come at sunset, and the mood softens. The light becomes amber, the coffers deepen in tone, and the dome itself seems to hover, its form fading slightly into the dusk. There’s something about that hour that makes the space feel less engineered and more… celestial. As if you’re inside a planet, or perhaps outside of time altogether.

And at night—if you’re ever fortunate enough to enter during a concert or vigil—the dome disappears into darkness, and all you see is the glow of candles below and a distant moon or star peeking through the oculus. It is, quite simply, otherworldly.

So yes, the Pantheon is a masterclass in engineering and symbolism. But more than that—it is a living, breathing experience of space. It teaches you not just about architecture, but about time, light, and your own sense of scale. No rendering or drawing can prepare you for it. And no visit feels exactly like the last.

Sources

Mark Wilson Jones, Principles of Roman Architecture (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 154.

Amanda Claridge, Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 258.

Vitruvius, Ten Books on Architecture, trans. Ingrid Rowland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), Book III.

Lynne C. Lancaster, Concrete Vaulted Construction in Imperial Rome (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 87.

Kim Williams and Lionel March, “The Pantheon: Proportional and Design Studies,” Nexus Network Journal 7, no. 1 (2005): 5–20.

David Moore, “The Roman Pantheon: The Triumph of Concrete,” Concrete International, vol. 17, no. 3 (1995): 56–63.

Ross King, Brunelleschi’s Dome: How a Renaissance Genius Reinvented Architecture (New York: Penguin, 2000), 44–45.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, trans. Gaston du C. de Vere (London: Everyman, 1996), 526.

Le Corbusier, Toward a New Architecture, trans. Frederick Etchells (New York: Dover Publications, 1986), 143.

Norman Foster, quoted in Deyan Sudjic, Norman Foster: A Life in Architecture (London: Phoenix, 2011), 128.

Author’s observation during site visit.

07-09-2023

Architects are not simply architects; they assume roles as caretakers of the community, defenders of the environment, pioneers of innovative design, and promoters of cultural diversity and inclusion in every aspect of their work. The core values are deeply ingrained, emphasizing the creation of spaces that empower, inspire, and connect individuals, all while preserving the Earth's invaluable resources.

Philosophy:

1. Community Engagement: The cornerstone of any successful architectural project lies in active community involvement. Architects immerse themselves in the local culture, collaborating closely with residents, stakeholders, and organizations to ensure that designs reflect the distinct identity and requirements of each community served. They view themselves as catalysts for positive change, cultivating a sense of ownership and pride among their collaborators.

2. Environmental Conservation: Sustainability isn't just a trendy term; it's an integral component of the design philosophy. There is a steadfast commitment to the responsible utilization of resources, the reduction of ecological impact, and the creation of buildings that seamlessly blend with their surroundings. From passive solar design to the use of eco-friendly building materials, every project strives to be an environmental success story.

3. Experimental Design: Architects consistently challenge the boundaries of conventional design. They embrace innovation, experiment with cutting-edge technologies and materials, and aim to create spaces that are both functional and visually captivating. The objective is to challenge preconceptions, ignite new dialogues, and inspire future generations of architects.

4. Cultural Diversity and Inclusion: Architecture holds the power to bridge cultural divides and celebrate diversity. Designs are a testament to their commitment to inclusivity, drawing inspiration from a rich tapestry of cultures, traditions, and viewpoints. They work tirelessly to ensure that their projects are inclusive, accessible, and welcoming to all.

Portfolio:

The portfolio reflects an unwavering dedication to these core principles. From sustainable housing developments seamlessly integrated into their natural surroundings to iconic cultural centers that honor the heritage of diverse communities, projects serve as evidence of their commitment to community, environment, innovation, and inclusivity.

20-08-2023

Forthcoming book “Straight Talking: Spatial Politics and Architectures of Squatting in Berlin” now available

Schwarzwohnen means “illegal living.” The practice can be traced to the occupation of a small apartment block in 1967 on Kleine Marktstraße in the East German city of Halle. Schwarzwohnen was not a marginal phenomenon. Thousands of citizens lived “illegally” in vacated buildings in the 1970s-80s in the German Democratic Republic, also known as East Germany. AM Kunsthaus Tacheles was celebrated as one of the most culturally significant squatter houses and alternative art centers in Berlin until it was vacated in 2012. Originally a grand 1902 department store, Tacheles, Yiddish for “straight talking,” was named by a group of Jewish artists who occupied the building after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. Due to the subsequent rise of interest in real estate and gentrification, many squatter houses were threatened by demolition. In 2012, the Tacheles was finally vacated after a 20-year battle for ownership with the artists in residence. Today the site has been rebuilt as luxury residences, (completed in 2022). Only a small part of the original 1902 building remains, and the artworks have been either demolished or moved to paid-entry galleries. The destruction of Tacheles represents a significant loss of city history and an erasure of many years and layers of artists’ work and culture. This book engages the existential battle over Tacheles. The research investigates tensions between the generic gentrified structure and the free space of the Berlin subculture that is battling for survival and trying to reclaim its original footprint. The design research creatively maps the complex history of the site and looks at strategies of cultural conservation that could save Tacheles in a way that celebrates the site’s historic significance while supporting new multicultural artistic communities.

20-09-2021

World Architecture Festival Drawing Competition: top 10 drawings of the year shortlisted

After a long and lengthy debate by the judges, I am pleased to know that the Propulsive omnibus cluster of architectural dream logic, has been selected for the shortlist top 10 drawings of the year

The drawing will be displayed at the John Soane Museum in London as part of the competition result exhibition

In his own words, Macro Polo says “The traveler’s past changes according to the route he has followed: not the immediate past, but the more remote past.”

Hand drawn on cotton paper. digitally rendered

30” x 45”